Artist Rimma Milenkova on Modern Artivism and Stolen Names of Ukrainian Artists

Despite popular belief, it’s not always the case that art is the result of creative inspiration. It can also be an expression of a traumatic experience: particularly the one that Ukrainians are currently experiencing. Modern creators use the language of art to tell the world the whole truth about the war in Ukraine. One of them is Rimma Milenkova, an artist, an art manager, and founder of the BureauArt gallery. Also, she was among the artists who joined our Revival Project, created with the aim of restoring Ukrainian cultural sites.

Rimma told us about her artistic and educational projects in Philadelphia and also shared her thoughts on wartime art and the need to rethink Ukrainian colonial heritage. Keep reading to learn more!

On symbols from childhood

I’ve been drawing since the time I could hold a pencil. My favorite activity made my parents happy because I used to disappear for many hours and made myself invisible to them. And it made me happy because I had my own world and could spend my time the way I wanted.

My childhood is associated with the green lake in Okhtyrka. There my cousin and I used to spend all our free time, as well as vacations. Above it, there was a school where my parents once met. They have been together since the second grade. Around the lake, there were huge trees that my father had once planted. And although they’ve already been cut down, human relationships keep on going. For me, this lake had become a beautiful symbol. That’s why many years later, I created an exhibition in the Okhtyrka Museum called “Emerald Lake.” The key artistic work at this exhibition was the eponymous painting depicting a green lake, a duck flying over it, and huge cut-down trees.

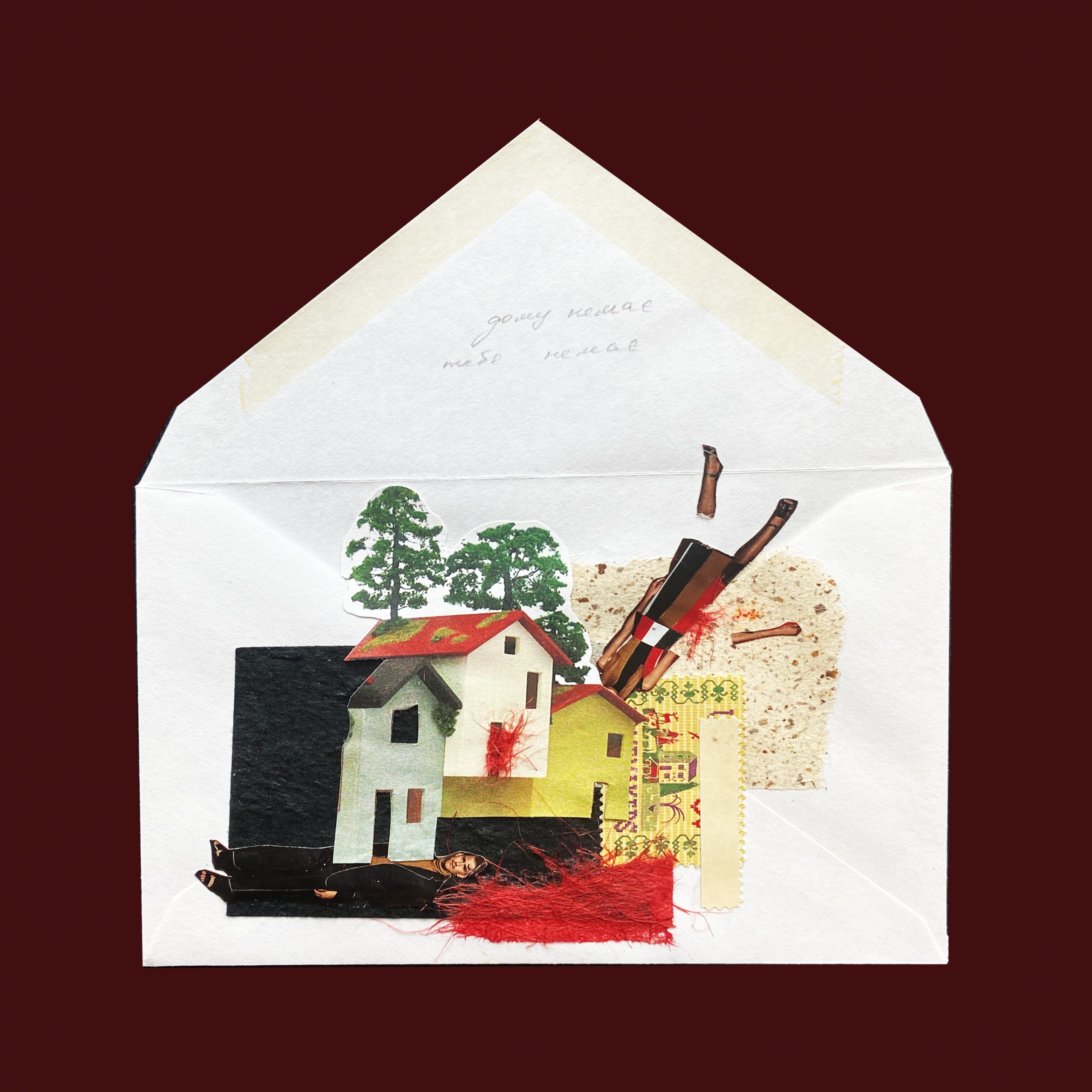

“There’s no home anymore.” Rimma Milenkova, 2022, paper, collage, “Unsent” series

On art as the search for identity

Initially, art was perceived as creativity, but what is creativity? It is what makes us like the religious idea of the creator, in image and in likeness. I mean, a person creates something and thus influences the world and reveals their essence. Speaking about art in a narrower context, it is a search for identity. During different periods of my life, I’ve been painting in different styles because each period lends itself to distinct color, technique, and emotions. For me, art has never been the main means of living. It is really a search for identity, because I always ask myself what I am worth as an artist, as a scientist, and as an art manager. The point is about evaluating myself and the world inside me. Art is not only about the aesthetics of an artwork, but also about what lies beyond that artwork. And this is extremely interesting. It’s always a great mystery and a large space for interpretations.

On wartime art

It seems to me that now artists are divided into two categories: those who have a place of strength and inspiration inside themselves and are able to produce artworks even during tragic times, and those for whom creativity is just a rethinking of what is happening.

I analyzed how Ukrainian artists reacted to terrible events and saw that many could not work. And there are also many of those who reinterpret the news visually, actually copying photos that appear online using different styles. I think artists today are just trying to digest all this poison and transmit it through themselves.

It turned out that I am not strong enough to generate new creative images during this period. So, I have focused on the easiest technique; I make small collages. I work with pieces from magazines, iconic pictures, texts, and textures to create large combinations. This is the reflection of my world.

“Premonition.” Rimma Milenkova, 2022, Glitch-Gif

On artivism

Visual art has always been connected with activism, and that’s the reason why the concept of artivism appeared. For example, in the United States, there were massive art protests that drew attention to the problem of AIDS or the Vietnam War. I see the same surge now on social media, especially in digital works. This is actually artivism, because social media have become platforms that replaced the streets and professional art galleries. This means that all art available on social media can be classified as public art. People see images on social media much more often than on the streets. It works much more efficiently by creating a public space inside the smartphone and consequently inside us. That’s why it is extremely important to support artivism online.

Here in Philadelphia, I was lucky to create several public projects on the war in Ukraine. Together with the well-known organization Mural Arts Philadelphia, we made a large projection on the wall of the Ukrainian League building. I had a chance to show paintings and digital works by Ukrainian artists such as Danylo Movchan and others who work with the aesthetic theme of war and create digital posters. We demonstrated these works to the music of Myroslav Skoryk, and recited poems in Ukrainian and English by Serhiy Zhadan, Ivan Malkovych, and other authors.

For me artivism online is a source of Ukrainian spirit, which I can show here, abroad, to attract attention. And doing it not using words, showing it not through a tragedy. Instead, showing the courage of Ukrainians and that Ukraine is not only ruined and gray. This is a country that has many colors and many talents we can show to the world.

“Texts and Visions of Ukraine” project in cooperation with Mural Arts Philadelphia, PA, USA. Projection of the Ukrainian artist Yurii Ivantsik’s artwork on the wall of the Ukrainian League of Philadelphia, May 2022. Project curator Rimma Milenkova.

On cultural misrepresentation

Currently, there is a distorted perception of Ukrainian art and wartime art. In the artworks of the first days, weeks, and months of the war, there was a lot of brutality. It was absolutely necessary for us because it is a way of survival. We’ve been taught to be nice to people and that’s great; but this works only in times of peace. We see art emerging now that urges us to stop being kind if someone breaks into your house and can kill you or your child.

How to show this to other nations that haven’t seen war? How to tell that we have the right to be cruel in certain situations? It’s an extremely delicate issue, and one that is likely not suitable for broad audiences. There are very strong restrictions to presentations in galleries and on the streets, because the psychological consequences of showing such works lie with the exhibition organizers. It’s a very serious responsibility. This is what the tragedy of art and our mission is: how to convey the emotion properly, to awaken the desire to support us while avoiding trauma. Because we have no right to pass on the trauma we have experienced to other people. People who visit our exhibitions shouldn’t cry. They should sign petitions and transfer donations. And it’s good if then they would think: “I am happy I’ve done this. I am proud I have supported Ukraine.” Because actually, we don’t need tears, we need support. I think I am able to achieve this by promoting Ukrainian visual art.

On self-identification of Ukrainian-born artists

I really want to create an artistic and scientific project on how Russians stole the names of Ukrainian artists such as Malevich who is still labeled as a Russian artist on the painting plaques at world museums. The same goes for Sonia Delaunay, Vladimir Tatlin, and Vasyl Yermylov. Or David Burliuk, who was born near Sumy, my homeland, and who is called the father of Russian futurism, but we call him the Ukrainian father of Russian futurism. I wonder what these people were like—people who used their own potential, their art, and at some point the Russian language as a currency for their own promotion. Why did these people do this, and how did they define their identity?

Now, we know for sure that national identity is not something inherited, not transmitted by genes, and not determined by language, but is a pure product of self-determination. If I determine myself as Ukrainian, I will remain Ukrainian no matter what country I live in. Among the Ukrainian-born famous artists of various genres, there are those who chose to be called Ukrainians and those who chose otherwise.

We need to provide a comprehensive promotion for those artists who throughout all their lives have been saying that their identity is Ukrainian, their origin is Cossack, and their patterns are based on Ukrainian ornamentation. And about those who were born here but never considered themselves Ukrainians, I think we can keep silent. Others will promote them.

“No, it’s impossible to escape.” Rimma Milenkova, 2022, paper, collage, “Unsent” series

On the art of the future

Art is unpredictable—especially now, when it is going digital. However, the existence of an NFT does not deny the existence of an integral physical object in any way. I think artworks will become more cross-disciplinary. I also wish that art in Ukraine would become more patriotic. Before the war, I was very disappointed that Ukrainian artists were so apolitical, especially the young ones. Even the exhibitions at the Venice Biennale were so noncommittal that their message was substandard. It seems to me that this war is going to turn our mindset upside-down, and we will begin to create only those works that bring out the best about Ukraine and show what a strong nation we are.

Other articles that may interest you:

Lviv-Based Artist Mykhailo Skop on Board Game Design, Medieval Art, and Wartime Posters